Icons Among Us: Room 222

It is the most famous classroom of all. Or was it?

By Caleb Daniloff B.U.Today)

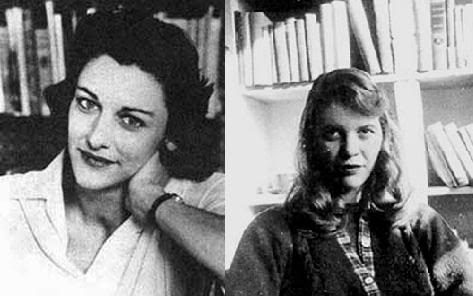

Legend has it that in the same room, Robert Lowell taught aspiring poets Anne Sexton, Sylvia Plath, and George Starbuck, all of whom went on to become pivotal figures in modern American poetry.

When I was in college, I had a terrific crush on the poet Anne Sexton, dead 20 years at the time. I was smitten by her confessional verse, the recordings of her voice inflating those tortured words.

Sexton’s mythology had me on my knees. The iconic photo of her sitting on a ledge in a swirl-patterned shoulderless dress, eyes raised skyward, legs twisted impossibly around one another, cigarette dangling from her fingers. Her story of morphing from suburban housewife to Pulitzer Prize winner to asleep forever in the front seat of her car; the drunkenness, hospitalizations, affairs, family abuse, suicide, all throttled my imagination. When I found out that my aunt had been pals with Sexton in high school, I devoured the inscriptions in her yearbook.

I moved on; she stayed fixed in time. But like a one-time high school flame friending me on Facebook, we reconnected a few weeks ago. At 236 Bay State Road, second floor, Room 222.

Room 222, or the Robert Lowell Seminar Room, is the central classroom for BU’s venerable Creative Writing Program. All graduate and advanced undergraduate writing classes are held here. Legend has it that Lowell (below), considered the father of confessional poetry, taught Sexton in this small room, along with Sylvia Plath and George Starbuck, in what is considered poetry’s most famous class.

“There was a period when many people would have said Lowell was the major poet of the post–World War II era,” says Bonnie Costello, a College of Arts & Sciences professor of English. “He had a major impact on the poets who came through Room 222. Sexton, Plath, W. D. Snodgrass, Starbuck — they had a lot in common. They all had breakdowns, were all in treatment. Most of them had children. It’s hard to know whether these people came to Lowell’s class because they recognized themselves in his work or it was coincidence.”

I met Robert Pinsky, a CAS professor of English and three-time U.S. poet laureate, in Room 222 to ask what the space “with a little glimpse of the Charles” means to him. Through the window, ivy thickens the walls of Hillel House across the road. Wooden desks creaked beneath us as if the doors of time were opening. I ran my hand over the worn surface and wondered if Sexton ever sat at this desk, scribbled nascent lines, cigarette in the other hand.

“Of all of the classrooms I’ve taught in — Harvard, Berkeley, University of Chicago, Stanford — this is my favorite,” Pinsky says. “The legend of Lowell teaching Plath, Sexton, and Starbuck is only part of it. I like the echoes. But I now have my own memories of all the students I’ve taught in this room over 16 years. And I like knowing that my colleagues Louise Glück, Leslie Epstein, Ha Jin, Rosanna Warren are using this room, too. I like knowing it’s ours.”

A few years ago, thanks to a generous graduate, Room 222 got a makeover: new windows, ceiling, recessed lighting, refinished floors, a blackboard (or greenboard). Another alum donated a Persian rug.

One of Pinsky’s former students, Maggie Dietz (GRS’97), now a CAS lecturer, head of the Robert Lowell Memorial Lecture Series, and herself a fine poet, remembers dull brown carpeting, a dropped ceiling, harsh lighting, and drafty windows. But it was the room’s feeling that was significant, she says.

“It felt intimate, and also serious, in part because I had the sense that it was historically charged,” Dietz says. “When you sit in a place where you think Plath and Lowell might have been, you just hope that through some kind of osmosis you might grow a little bit as a poet and become worthy of having sat in the room.”

Today, Dietz sees her own students starry-eyed and open to possibility. She points out that Sexton, who won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 1967, and Plath (above), author of The Bell Jar and posthumous recipient of the 1982 Pulitzer for poetry, were unknown students writers at the time, just like they are, just like she was. Sexton was a troubled stay-at-home mom dabbling in poetry at her therapist’s suggestion, while Plath was just auditing.

“BU is such a big school, to come here and be treated like artists, to be poets for a long afternoon once a week, is special,” Dietz says. “To feel like they’re allowed entry into this space where it’s only writers who come in, only writers who meet and talk about their work, is exciting. It’s not like their other classes. It’s warm and the radiator clunks. It’s cozy. You watch the ivy change on Hillel House as it goes from red to bare.”

In the early ’90s, the room’s legend was further juiced, this time on the fiction side. The program produced future Pulitzer winner Jhumpa Lahiri (GRS’93, UNI’95,’97), National Book Award winner Ha Jin (GRS’92), and acclaimed writers Peter Ho Davies (GRS’92) and Daphne Kalotay (GRS’93). Sue Miller (GRS’80) and Arthur Golden (GRS’88) helped pave the way in the previous decade. Poetry wasn't slouching, either, churning out Carl Phillips (GRS'93) and Erin Belieu (GRS'95), among others. Heavyweight guest lecturers have held forth over the years, too: John Cheever, Donald Barthelme, John Barth, Norman Mailer, Amos Oz. Room 222 has taken on the quality of an organic museum, a vessel for the collective literary imagination.

But doubt has been cast on the facts of the creation myth. So I phoned longtime department administrator Harriet Lane (DGE’55, CAS’57, GRS’61), who retired last year after a 50-year tenure and had been enrolled in the program in the 1950s. Her late husband took classes with Lowell. Lane says other departments occupied the second floor when Lowell taught at BU, and that like other English professors, he was assigned random, generic classrooms in the CAS building.

“At that time, the English department was only on the fourth floor of the brownstone on Bay State Road,” Lane says. “In fact, in one of his poems, Lowell refers to a room in which he taught as a ‘shoebox.’”

Lane says she later found and installed the 15 desks still in Room 222 when the Creative Writing Program moved to the second floor, some time after the mythical heyday.

I felt deflated, but as Dietz says, what matters is that these future titans of poetry met together on campus, not where they sat. I perked up when Lane described Sexton, who later taught at BU, as “charming and articulate” and said that “her students thought very highly of her.”

Pinsky and Dietz think it’s possible the room was informally commandeered. “I’d bet Lowell did teach a class here,” Pinsky says. “It might have been some weird outrider that this was consigned as a space.”

Starbuck went onto to become director of the program, and his one-time colleague and successor Leslie Epstein supports 222’s pedigree. “This was the room,” he says. “That’s what George told me, and as far I know, it’s the truth.” Then again, Epstein points out, more often than not the class met at the Ritz Lounge over drinks, parking their cars in the “loading zone,” as Starbuck, who died in 1996, used to joke.

Regardless, the whiff of mystery feels appropriate. Art is about reconciling perception and reality, illuminating the truth rather than defining it. The lessons taught in 222 apply to itself.

While Epstein appreciates the room’s persona, students are here for the business of writing, so he strives to put their awe on the shelves along with the literary journals.

“It’s impossible to teach with a sense of awe,” he says. “I expose my prejudices, my likes and dislikes, my flaws, because the whole year is dedicated to noticing flaws. I don’t want to build up a sense of awe about the room. You’re not supposed to eat in there — we eat in there. Not supposed to drink in there — we drink in there. I used to make my students do push-ups. It’s a place where we violate rules. You can’t be a writer if you don’t violate rules, be a little subversive.”

In that spirit, I tattoo in my mind the image of a bright-eyed Sexton in Room 222, back-and-forthing with a disheveled Lowell, a cloud of smoke in the air, Plath jealously looking on.

I choose to believe.

Sunday, December 13, 2009

Tuesday, December 1, 2009

Poets die young....

He died from a love of poetry

Marc Abrahams The Guardian, Tuesday 18 March 2008

Poets, by tradition, imagine themselves likely to die young. But that's not a matter of imagination, says Associate Professor James C Kaufman, of California State University at San Bernardino. It's a simple fact.

Kaufman looked at the lives and deaths of 1,987 deceased writers from four different cultures: American, Chinese, Turkish and eastern European. His 2003 study, The Cost of the Muse: Poets Die Young, paints a mathematically ghoulish picture. Poets drop off earliest, Kaufman explains, but authors in general are not a long-lived bunch.

He writes that: "The image of the writer as a doomed and sometimes tragic figure, bound to die young, can be backed up by research. Writers die young. This research finding has been consistently replicated in a variety of studies."

Before dissecting the body of evidence about poets, Kaufman visits that much larger corpus of published research about writers in general. A 1975 study found that poets tended to die younger than fiction writers. A 1995 study found that "poets died younger than fiction writers, non-fiction writers, and people in the theatre". A 1997 study "found that Japanese writers were more likely to die young than other eminent Japanese". And so on.

Kaufman also mentions, in passing, that a 1985 study by a researcher named Koski "found that some Finnish writers used alcohol to stimulate writing".

Kaufman's own research covers an expanse of time as well as geography - North American authors born as early as 1612, Chinese writers with birthdays as early as 1852, Turkish writers born after 1343, and eastern European writers whose birthdates range back as far as the year 390. In their ranks are, or rather were, fiction writers, poets, playwrights and non-fiction writers.

Kaufman used a statistical tool called Tukey's Honestly Significant Difference test "to determine which differences were significant in each culture, by gender, and overall".

The numbers tell the story. A poet's life, on average, is about a year shorter than that of a playwright, four years shorter than a novelist's life, and five-and-six-tenths years less than that of a non-fiction specialist.

Kaufman's study ends, as do the lives of many poets, on a sad note. He writes: "The fact that a Sylvia Plath or Anne Sexton may die young does not necessarily mean an introduction to poetry class should carry a warning that poems may be hazardous to one's health. Yet this study may reinforce the idea of poets being surrounded by an aura of doom, even compared with others who may pick up a pen and paper for other purposes. It is hoped that the data presented here will help poets and mental-health professionals find ways to lessen what appears to be a sometimes negative impact of writing poetry on mortality and mental health."

· Marc Abrahams is editor of the bimonthly Annals of Improbable Research and organiser of the Ig Nobel prize

Marc Abrahams The Guardian, Tuesday 18 March 2008

Poets, by tradition, imagine themselves likely to die young. But that's not a matter of imagination, says Associate Professor James C Kaufman, of California State University at San Bernardino. It's a simple fact.

Kaufman looked at the lives and deaths of 1,987 deceased writers from four different cultures: American, Chinese, Turkish and eastern European. His 2003 study, The Cost of the Muse: Poets Die Young, paints a mathematically ghoulish picture. Poets drop off earliest, Kaufman explains, but authors in general are not a long-lived bunch.

He writes that: "The image of the writer as a doomed and sometimes tragic figure, bound to die young, can be backed up by research. Writers die young. This research finding has been consistently replicated in a variety of studies."

Before dissecting the body of evidence about poets, Kaufman visits that much larger corpus of published research about writers in general. A 1975 study found that poets tended to die younger than fiction writers. A 1995 study found that "poets died younger than fiction writers, non-fiction writers, and people in the theatre". A 1997 study "found that Japanese writers were more likely to die young than other eminent Japanese". And so on.

Kaufman also mentions, in passing, that a 1985 study by a researcher named Koski "found that some Finnish writers used alcohol to stimulate writing".

Kaufman's own research covers an expanse of time as well as geography - North American authors born as early as 1612, Chinese writers with birthdays as early as 1852, Turkish writers born after 1343, and eastern European writers whose birthdates range back as far as the year 390. In their ranks are, or rather were, fiction writers, poets, playwrights and non-fiction writers.

Kaufman used a statistical tool called Tukey's Honestly Significant Difference test "to determine which differences were significant in each culture, by gender, and overall".

The numbers tell the story. A poet's life, on average, is about a year shorter than that of a playwright, four years shorter than a novelist's life, and five-and-six-tenths years less than that of a non-fiction specialist.

Kaufman's study ends, as do the lives of many poets, on a sad note. He writes: "The fact that a Sylvia Plath or Anne Sexton may die young does not necessarily mean an introduction to poetry class should carry a warning that poems may be hazardous to one's health. Yet this study may reinforce the idea of poets being surrounded by an aura of doom, even compared with others who may pick up a pen and paper for other purposes. It is hoped that the data presented here will help poets and mental-health professionals find ways to lessen what appears to be a sometimes negative impact of writing poetry on mortality and mental health."

· Marc Abrahams is editor of the bimonthly Annals of Improbable Research and organiser of the Ig Nobel prize

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)